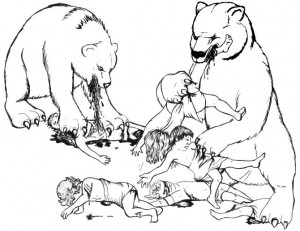

Earlier this week, I authored a piece elaborating on my response to a variation of a moral argument for God’s existence Reverend Brewster presented in our August 31 “Does the Christian god exist?” debate (watch video footage or listen to an audio-only recording for more context). Since the debate and my piece, Reverend Brewster has engaged in discussion on my Facebook page responding to challenges positing that the Christian god may not be all-loving because of atrocities in the Bible such as God sending she-bears to kill 42 young boys.

Reverend Brewster, in response to Bible passages suggesting the character of God is not all-loving, states that we can’t comprehend morality in its “fullest sense because we are unable to see the end of things.” He also suggests that what we might believe to be immoral now may actually not be immoral in the long-run under God’s plan.

Brewster — rather than relinquishing belief in an all-loving god when presented with evidence to the contrary — implies that God, for all we know, may have some undetectable and incomprehensible reasons for sending she-bears to kill young boys. The ‘mind of God’ is just too big to understand for us humans, Brewster implies.

This position renders theistic belief irrational because any given challenge to God’s existence may be easily ‘excused away.’ Nothing, under this ‘we cannot understand the mind of God’ position, can render belief in God false. Lacking a situation in which God may not exist, the theist is utterly close-minded and unwilling to reconsider their belief; no evidence can serve as reason to disbelieve.

One wonders, under this position, why theists would not be agnostic about the moral character of God because, if, for all we know, there may be undetectable reasons for God committing atrocities — even though he is said to be all-powerful and all-knowing which would allow him to achieve certain ends without sending she-bears to kill children — and atrocities may actually not be so bad after all, we should also be forced to admit that good actions God may command, for all we know, may not be good and are instead part of an evil or not-so-good master plan. The razor must cut both ways.

Worse yet, the ‘we cannot know the mind of God position’ ought to force us to a position of moral skepticism although all of our moral intuitions dictate otherwise. An Indian Ocean tsunami which kills thousands of people may, for all we know, under Brewster’s view, be part of God’s plan to achieve some unknown goal – thus the tsunami is actually a good thing and helping survivors by donating to the Red Cross is interfering with God’s plan. Perhaps those who were harmed should not be pitied and helped, but rather are blessed and should be left to suffer?

If we are going to fail to acknowledge actions are immoral because we may lack understanding although our moral intuitions point to acts being immoral, why stop at God’s plan? Why not say that, for all we know, Hitler may have had really good reasons for ordering extermination of Jews and that we can’t say this is a bad thing because we’re unable to see “the end of things” and can’t comprehend morality in “its fullest sense?” Why would the theist — willing to admit that God may have undetectable reasons for committing atrocities — not also extend this to humans? After all, we may lack information that other humans are privy to just as we — under the theistic view — lack information God is privy to.

Rather than excusing away evidence against the Christian god with an unlimited supply of ‘we just cannot know the mind of God,’ we should relinquish belief in God when contrary evidence is presented.